English spelling is ridiculous and outrageous to most eight year olds. Or wait, is it outragous and ridiculeous? Humorous or Humoreous? Is the laughter contagious? Or contageous? Or contagous? And why? Why is spelling in English so tricky? And knowing how tricky it is, how best teach it?

To answer that question, we’re delighted for the sage wisdom and collaboration of Dr. Molly Ness, Associate Professor at Fordham University. Molly is a fellow word nerd and a champion of the critical role of spelling in early literacy instruction. When she’s not reading, she’s writing and teaching about reading. Our kind of fun as well! After working together on the piece, Dr. Ness was nice enough to let us record a quick conversation about the article, the importance of spelling, and what's on her reading list these days.

We also need to thank Deborah Reed, whose work Why Teach Spelling and its citations are heavily referenced by this post.

So, Why Teach Spelling?

Harkening back to the days before auto-correct, spelling was taught because writing was so important. Your spelling was, and is, a signal to the reader of your level of education. Even now, spelling remains a critical component of literacy instruction, but the role and rationale of teaching spelling has changed substantially.

Spelling and reading are grounded in the same mental model of a word. They are two sides of the same coin, “encoding” and “decoding”. So it follows that the better we teach children to spell, the better they will learn to read. (Snow, Griffin, and Burns (2005).

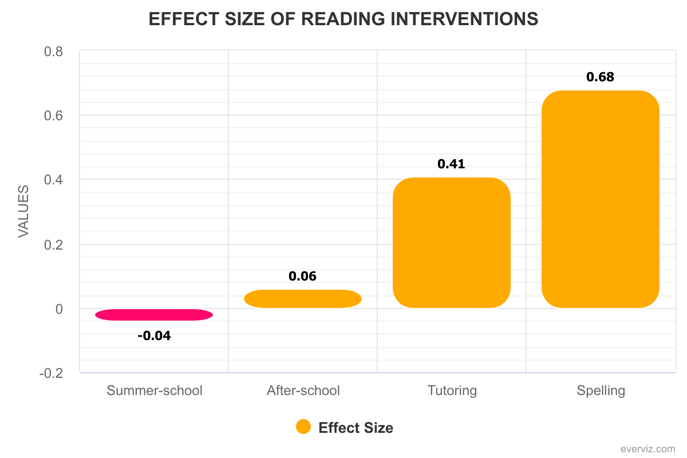

In the study of “impact” on reading scores, we talk about Effect Size. I’ll do a blog post someday to try to explain what that means and how it is calculated, but as a quick comparison, the effect size of the top-tier tutoring programs is +.41, of summer-school is -.04 (yep, negative!), of after-school is +.06. The effect size of the high-quality spelling instruction Dr. Ness describe below is +.68 to +.79. Teach kids to spell and they become significantly better readers.

These results make sense, especially if you believe as strongly as we do in "self-teaching". This theory, based on the work of Dr. David Share, is centered on the idea that it is up to the student to teach themselves to read, one word at a time. A teacher can be a guide, but not a cheat sheet. A student must put together the sounds of a word with the letters they see, that is when they are truly learning.

And this is why spelling is so important. You are forcing an explicit interaction between the sounds the student hears and the letters they write. Because they write it down, it has to come from within. They make their best guess, and in that productive activity, they are hyper-focused on the specific letters in the word. This is the extremely high-quality practice that leads to learning to read.

So How Do We Teach Kids to Spell Better?

As with anything in literacy, there are a number of potential approaches to teaching anything. Let’s take a look at three teachers and study what they do and why.

Three Options

- Loquacious Lyndsey teaches spelling based on the curriculum she is using currently in the classroom. If they are working on the Arctic, she will focus on spelling word lists that include things like “polar bear”, “fox” and “snow”. She often walks around while students are writing in class and helps correct spelling errors as she goes, keeping these tricky words on a list so all students can work through them later. Her students practice by studying a word, copying it, covering it, and then trying to spell it from memory.

- Erudite Emily approach to spelling is quite different. Instead of connecting word lists to the curriculum, she teaches spelling independently, starting from simple CVC words using short vowel sounds. Her students practice by encoding (writing down) words she says out loud. Eventually, she moves into larger words and patterns, like TH and SH digraphs and doubled vowels. Then she starts introducing more advanced spelling rules with groups of similar words like DOUGH, THOUGH, TOUGH and ROUGH.

- Scholarly Sam has a different strategy, though he starts off similar to Emily by teaching basic spelling with CVC words. But after that, he starts to teach spelling through grammar. He does lessons on how to make words plural, and how to add ED and ING to make past tense or gerunds. He points out the connection between words like SIGN and SIGNAL and how they share a similar kind of meaning, as well as spelling.

As a teacher, you know just how important it is to ask some questions and get the brain thinking a bit to ensure comprehension. Take a moment or two to think about these three teachers’ stories and answer a few questions:

- If you had to label these approaches, what would you call them?

- Which of these is easier to teach? Which is the hardest?

- Which do you think would produce the best results?

- Do you think the results would change if you had students that were from a low-income community vs. teaching in a private school?

Thoughts on the Common Teaching Strategies

At face value, all three strategies have merits, but let’s look deeper. Lyndsey is using a whole-language approach, which feels really natural. Word lists come from the content kids are reading.

The challenge, though, is that these words are not likely to be highly related to each other linguistically. You'll see better results if you teach similar words together as a set. Otherwise, you need to memorize them with rote memorization skills, which doesn't commit the spellings nearly as well to long-term memory.

While it may seem like reinforcing the content the kids are reading is a natural bridge to proper spelling, teaching better spelling can actually drive the reciprocal relationship between decoding and encoding.

On the bright side, Lyndsey is leveraging the science of reading big time by providing immediate feedback on spelling mistakes by the students. This near-real-time correction is critical to helping students make gains (Wanzek et al., 2006).

The phonics approach, used by Emily, does a great job of creating a thoughtful progression of words based on their spelling complexity. The challenge here is that phonics alone just isn’t enough to spell most words in English. 97% of words contain some kind of spelling exception, including many of the most common words in the language.

So we're going to need to go deeper and explain the more advanced rules that guide the spelling, as well as the countless exceptions to those "rules".

But beware the phonics rabbit hole!

When the focus of the exercise is too narrow (e.g. lots of decoding of lots of words), we’re leaving a good book on the table.

Ideally, after we teach a set of spelling patterns and words that follow them, we want to then work with those words in print. We want the student to be keenly aware that as they learn to spell the word, they also can read it. Seeing the word in context also helps cement the student’s learning, so they will be more successful both reading and writing the word the next time.

Dr. Molly Ness

This aspect of instruction is addressed at some level by Sam, who is focusing on the morphology of English as it comes up in the words he has selected for his class to learn. Words like SIGN and SIGNAL come from the same concept, that’s why we spell them the same. But they sound different, because they were used in different ways, more or less often, by different people with different accents, and over time each transformed in its own way.

But this strategy, and in fact any of the above on their own, isn't making the maximum use of your time as a teacher. So what's the best practice?

Five Essentials to Effective Spelling Instruction

With spelling (as with reading), the science has progressed so rapidly in the past ten years that it is very hard to keep up. Thankfully, Dr. Ness helped us collect some of the key battle-tested methods of spelling instruction that truly rise above the pack and are perfectly aligned to the current “best practice” as informed by research. Here are the five keys (and one bonus tip!) to unlock successful spelling for your students:

- Create Effective Spelling Lists Based on Common Linguistic Features: Wow a Cow?! Teach spelling right now! Word lists should be created using words with a common “rime” or ending string of letters. Rimes will rhyme, but they also have the same spelling: BEAR and CARE rhyme, but the rimes are EAR and ARE. The best spelling lists would add WEAR to the list with BEAR and SHARE to the list with CARE. These lists should be carefully matched to a student's cognitive capability and reading skill level.

- Prefixes, Roots, and Suffixes: Throughout your reading and spelling instruction, focus attention when you can on the underlying structures behind our words, like Sam did in the example above. This focus can substantially improve outcomes both for regular students (Devonshire & Fluck, 2010) and for those with dyslexia (Tsesmeli & Seymour, 2008). A simple takeaway here is to practice spelling with ED endings.

- Teach-Test-Study-Test: Students will not magically become master spellers. We have to teach them the patterns before we hold them accountable for knowing the patterns. Using TTST allows us to benchmark student performance and study words where spelling is between 50-85% known, the optimal range for pre-test scores to maximize gains (Morris et al., 1995).

- Look-Say-See-Write-Check: Lyndsey was so close! But to eek out the best in your spelling instruction, students need to say the word out loud; making a phonological representation of the words helps cement it in the student’s lexicon. Encourage them to think about the sounds in the words and how they relate back to the letters they see. Then cover up the text and write the word, followed by a quick check to correct any mistakes. Bingo!

- Read the Words You Spell: After working through lists of spelling words, find ways to engage with them naturally in text with your students. This is key to demonstrating the value of spelling: if you can spell the word, you can read the word. And reading rocks!

Bones TIP: Use Elknonin Boxes.

Another fantastic exercise (which is, ahem, nicely embedded into the TIPS™ worksheets in our own program) is the use of Elknonin Boxes. Again, the idea is to connect back the ideas of sounds to the letters that make them, even though these connections can be a bit irregular. A picture is worth a thousand words:

How About Spelling with TIPS?

Glad you asked.

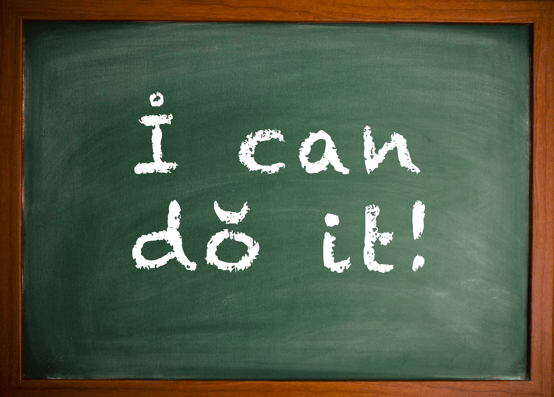

As you know from our site, TIPS™ (short for the TinyIvy Phonics System) is a system of diacritics we created to allow every word in English to be written in a way that is perfectly decodable. You can see examples over the I and the O on the chalkboard below.

We know from our pilots that TIPS are helping children learn to read faster than traditional methods, but how about spelling? Yep. It helps there too.

Faster achievement of Stage 1 and Stage 2 spelling.

Spelling progress is typically divided into Stages, the first two being Emergent and Letter Name / Alphabetic Spelling. TIPS™ naturally allows students to develop a deep knowledge of the letter-sound principle: that a letter makes a sound. Because of this, they typically attempt writing earlier. Of students who have been tutored with TIPS™, we see 3 and 4-year-olds labeling their drawings.

Invented spellings are more accurate.

Because TIPS includes marks for the /aw/ sound in SMALL and the /oiy/ sound in TOY, students have known options they can use to write these sounds, even in the first 6-10 weeks of instruction. This allows accuracy for guessed spellings to increase. And since TIPS™ are introduced in order based on their frequency of occurrence, the student is more likely to guess the correct spelling (since the correct spelling is likely the most common TIPS™ letter for this sound).

TIPS™ reading compliments effective spelling instruction

To learn to read with fluency, a student must effortlessly read thousands of words. Each word is learned one at a time. This means that to learn to read, students must read millions of words. That includes all those darn exceptions!

What makes TIPS™ so revolutionary is that we enable teaching to be clear and explicit, every sound is clearly marked in the word. Ultimately, this draws more attention to the idea that letters and sounds are connected in the decoding process. When taught to best practice, this makes spelling a little less mysterious, and therefore its instruction more effective.

That's a Wrap

We should stress that spelling in English is very, very hard. It takes years to learn. But it is important. Even in the age of auto-correct.

While it may seem one thing to see a word and read it and another entirely to hear a word and write it down, recent research shows that this is not at all the case. How we learn to read and how we learn to spell are inextricably linked. If we teach both, students bloom.

If we teach both well, they skyrocket.